CONCERT CANCELLED

With great regret Allegheny RiverStone has cancelled the March 1 Concert of the Alexander String Quartet with Alec Chien due to the snow event bringing 5 -8 inches of snow to western Pennsylvania and freezing rain to Pittsburgh later in the afternoon. ARCA members will be notified of a date for a rescheduled reception for Bronze and above Members at RiverStone Mansion later in the season.

__________________________________________

Celebrated for their performances of “uncompromising power, intensity and spiritual depth”, the internationally acclaimed Alexander String Quartet will return to Lincoln Hall on Sunday, March 1 with pianist, Alec Chien to open ARCA’s 2015 season. They promise to warm your hearts and lift late-winter spirits with passionate and soulful performances of master chamber works – truly world class music making right here in the Allegheny River Valley. Join us and be inspired by these consummate artists who critics have said “seemed not so much to be playing the music as breathing it.”

ARCA membership donations of $100 and above which are received before March 1 will entitle those Bronze and above members to attend a post-concert Meet the Artist reception at RiverStone Mansion with the Alexander String Quartet. You may Become a Member online entitling to you to experience this wine and cheese reception at the stately and beautiful RiverStone estate.

Alexander String Quartet

PROGRAM NOTES

By Eric Bromberger

String Quartet in B-flat major, K. 589

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg

Died December 5, 1791, Vienna

In the spring of 1789, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, a generous patron of music, invited Mozart to visit Berlin with him. Legend has it that the cello-playing King Friedrich Wilhelm II was desperate to receive Mozart, who played before the king and queen and was rewarded with a golden snuffbox full of a hundred louis d’or and a commission to compose six string quartets for the king and six easy keyboard sonatas for his daughter. Mozart returned to Vienna but was able to complete only three of these quartets, thereafter nicknamed the “King of Prussia Quartets,” and then had to sell them for quick cash during the poverty of his final years.

But the problem is that this tale appears to have been a complete fabrication on Mozart’s part. While Mozart did visit Berlin in May 1789, all the evidence suggests that the king did not receive him, gave him no gift, and commissioned nothing. Faced with having to return to Vienna in utter defeat, Mozart borrowed money to pass off as from the king and created the story of the commission. Certainly he did not seem to take the commission – if it ever existed – very seriously: he wrote one quartet immediately, two a year later, and then forgot about the whole thing, and when these quartets were published there was no hint of a royal dedication (in his biography of Mozart, Maynard Solomon discusses in some detail the implications of this distressing episode). This should not cause us to undervalue these quartets, but it does present them in a different light than the legend would have it.

The three quartets he completed, however, have inevitably been nicknamed the “King of Prussia” quartets. Taking an obvious cue, Mozart made sure that all three feature an important role for the cellist, but such prominence created special problems for Mozart, who was essentially a “top-line” composer: he preferred to have the melody in the highest register, the accompaniment beneath it. As soon as the bottom voice is given prominence, the other three voices must have their roles re-defined. As a result, all four instruments have very active roles, giving these quartets an unusually rich sonority.

The Quartet in B-flat major, completed in May 1790, is relaxed and agreeable music. There is a sense of smoothness throughout the first movement. Its opening theme flows easily in the first violin, and the second subject – specifically given to the cello – proceeds along a steady pulse of eighth-notes; the surprisingly short development section makes frequent use of triplet rhythms. The cello has the main theme of the Larghetto; textures grow complex here, with ornate rhythms and unusual pairings of instruments: the first violin and cello, though some distance apart in range, share the material at times.

The cello fades from prominence over the final two movements. The Menuetto is in many ways the most impressive movement of this quartet. Much of the writing in the opening section sends the first violin quite high in its register, perhaps as an effort to balance the deep sonority of the cello. The trio section is huge: over a busy, chirping accompaniment, the first violin begins to develop material from the minuet, and Mozart stays with this until the third movement becomes, surprisingly, almost the longest in the quartet. The finale, much more conventional, flows smoothly on its 6/8 meter, and many have felt that its main theme bears a close relationship to the finale of Haydn’s “Joke” Quartet. The movement drives to an almost operatic climax with the first violin soaring high above the other instruments before the music subsides to its nicely understated close.

String Quartet No. 4 in D major, Op. 83

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH

Born September 25, 1906, St. Petersburg

Died August 9, 1975, Moscow

The Soviet crackdown on composers in February 1948 remains, over half a century later, one of the most devastating examples of government interference and censorship in history. Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Khachaturian, Miaskovsky, and others were excoriated for their “formalistic distortions and anti‑democratic tendencies” and for writing “confused, neuropathological combinations which transform music into cacophony.” These composers apologized and–in those frosty early days of the Cold War–promised to write more “progressive” music, in tune with the ideals of the Revolution.

Shostakovich, who had met with government disfavor in 1936 during the period of Stalin’s “Great Terror,” began to write two kinds of music. The “public” Shostakovich wrote what would now be described as politically‑correct scores, intended to satisfy Soviet officials with their ideological purity: the oratorio Song of the Forests, the cantata The Sun Shines over Our Motherland, the film score The Fall of Berlin, and a choral cycle with the numbing title Ten Poems on Texts by Revolutionary Poets. The “private” Shostakovich, however, wrote the music he wanted to, but held it back, waiting for a more receptive climate. The death of Stalin in March 1953 brought a political and artistic thaw, and Shostakovich could bring out these scores: the First Violin Concerto, composed in 1947, but not premiered until 1955; the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry, written in 1948 and first performed in 1955; and the Fourth and Fifth String Quartets, written respectively in 1949 and 1952, but not played until 1953.

Shostakovich’s Fourth String Quartet is almost as interesting for what it is not as for what it actually is. This music is remarkable for its restraint. All four movements are at a moderate tempo (three Allegrettos and one Andantino), and the work is marked by an emotional reserve as well. There are no dramatic extremes here – this music is spare, understated, lean, at times almost bleak. Harmonically, it varies moments of simple diatonic melodies (even unisons) with episodes of grinding dissonance. And at the end it fades into silence on the same note of emotional restraint that has marked the entire quartet.

The opening Allegretto is quite brief (only three minutes), just long enough to lay out two themes but not long enough to develop them in a significant way. The music moves from the quiet beginning, built on constantly-changing meters, to a full-throated restatement; more lyric secondary material leads to a quiet close on a unison D three octaves deep. The Andantino at first feels somewhat more settled. Its wistful opening, which belongs largely to the first violin, is in straightforward F minor, but again the music grows more turbulent as the movement proceeds; it closes with a quiet reprise of the opening material, now played muted.

The third movement (which remains muted throughout) is scherzo‑like in its fusion of quick‑paced themes, from the cello’s propulsive opening to a more animated second subject; in the course of the movement, each of the four instruments takes a turn with this second melody. Unmuted solo viola leads the way into the finale over pizzicato accompaniment from the other voices. The first violin’s main theme here has a pronounced “Jewish” character – it is a lamenting tune, built on tight intervals, sharp accents, and fleeting dissonances. This movement, longest in the quartet, rises to an almost orchestral climax full of tremolos, unisons, and huge chords, then fades away on a haunting coda as the two violins in fourths restate the main theme. Over a sustained cello harmonic the upper voices lapse into silence on quiet pizzicatos.

Small wonder that Shostakovich kept this music hidden during the Stalin years. It is far from the “progressive” and popular music the Soviet government wanted, and while this quartet has been admired for its lucidity, it is nevertheless troubling music, remarkable for its leanness, its restraint – and for its bleakness.

Quintet for Piano & Strings in E-flat major, Op. 44

ROBERT SCHUMANN

Born June 8, 1810, Zwickau

Died July 29, 1850, Endenich

On September 12, 1840, Schumann married the young piano virtuosa Clara Wieck, a match that had been bitterly opposed by her father. With his father-in-law’s lawsuits and assaults on his character behind him, Schumann settled down to one of the happiest and most productive phases of his life, and his interests appeared to change by the year. From 1840 came a series of song-cycles, from 1841 a number of symphonic works, and in 1842 Schumann turned to chamber music. But this was not an easy transition for a composer who did not play a stringed instrument, and the three string quartets he wrote that summer gave him unusual difficulty. And so it must have been with some relief that Schumann fused the string quartet and the piano in his next composition, a Piano Quintet that he began on September 23 and completed October 12. The first performance, a private one with Clara at the piano, took place in November. A second performance was scheduled in the Schumann home on December 8, but Clara was sick and so Mendelssohn replaced her and sightread the piano part; the members of the Gewandhaus Quartet (whose first violinist Ferdinand David would three years later give the first performance of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto) were the other performers. That would have been an evening to sit in on, not just for the distinction of the performers but also to watch two composers at work: at the end of the read-through, Mendelssohn suggested several revisions, including replacing one of the trio sections of the scherzo, and Schumann followed his advice.

Schumann’s Piano Quintet is his most successful chamber work. The addition of the piano – Schumann’s own instrument – to the string quartet seems to have inspired him in a way the quartet form did not, and this is the first great piano quintet, to be followed over the next century by those of Brahms, Franck, Dvořák, and Shostakovich (though in fairness it should be noted that Mozart may have beaten him to it, having specified that several of his piano concertos could be performed as piano quintets). Schumann’s piano quintet has a clear star: the piano is the dominant force in this music – there is hardly a measure when it is not playing – and Schumann uses it in different ways, sometimes setting it against the other four instruments, sometimes using all five in unison.

The opening is a perfect example of the latter. This aptly-named Allegro brillante bursts to life as all five instruments shout out the opening idea, whose angular outline will shape much of the movement. Piano alone has the singing second subject: Schumann marks this dolce as the piano presents it, then espressivo as viola and cello take it up in turn. This second theme may bring welcome relief, but it is the driving energy of the opening subject that propels the music, and–built up to nearly symphonic proportions – it powers the movement to a resounding close.

The second movement – In modo d’una Marcia – is much in the manner of a funeral march, though Schumann did not himself call it that. The awkward tread of the march section – in C minor – is interrupted by two episodes: the first a wistful interlude for first violin, the second – Agitato – driven by pounding triplets in the piano. Schumann combines his various episodes in the final pages of this movement, which closes quietly in serene C major. The propulsive Scherzo molto vivace runs up and down the scale, and again Schumann provides two interludes: the first feels like an instrumental transcription of one of his songs, while the second powers its way along a steady rush of sixteenth-note perpetual motion.

The last movement is the most complex, for it returns not just to the manner of the opening movement but also to its thematic material. This Allegro, ma non troppo begins in a “wrong” key (G minor) and only gradually makes its way to E-flat major; while its second theme, for first violin, arrives in E major. At the climax of this sonata-form structure, Schumann brings matters to a grand pause, then re-introduces the opening subject of the first movement and develops it fugally, ingeniously using the first theme of the finale as a countersubject. It is brilliant writing, and it drives the Quintet to a triumphant close.

Clara Schumann, perhaps not the most unbiased judge of her husband’s work, was nevertheless exactly right in her estimation of this music. In her diary she described it as “Magnificent – a work filled with energy and freshness.”

THE ALEXANDER STRING QUARTET

Having celebrated its 30th Anniversary in 2011, the Alexander String Quartet has performed in the major music capitals of five continents, securing its standing among the world’s premier ensembles. Widely admired for its interpretations of Beethoven, Mozart, and Shostakovich, the quartet’s recordings of the Beethoven cycle (twice), Bartók, and Shostakovich cycle have won international critical acclaim. The quartet has also established itself as an important advocate of new music through over 25 commissions from such composers as Jake Heggie, Cindy Cox, Augusta Read Thomas, Robert Greenberg, Martin Bresnick, Cesar Cano, and Pulitzer Prize-winner Wayne Peterson. A new work by Tarik O’Regan, commissioned for the Alexander by the Boise Chamber Music Series, will have its premiere in 2016.

The Alexander String Quartet is a major artistic presence in its home base of San Francisco, serving since 1989 as Ensemble in Residence of San Francisco Performances and Directors of the Morrison Chamber Music Center in the College of Liberal and Creative Arts at San Francisco State University.

The Alexander String Quartet’s annual calendar of concerts includes engagements at major halls throughout North America and Europe. The quartet has appeared at Lincoln Center, the 92nd Street Y, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York City; Jordan Hall in Boston; the Library of Congress and Dumbarton Oaks in Washington; and chamber music societies and universities across the North American continent. Recent overseas tours have brought them to the U.K., the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, France, Greece, the Republic of Georgia, Argentina, Panamá, and the Philippines. They will return to Poland for their debut performances at the Beethoven Easter Festival in 2015.

Among the fine musicians with whom the Alexander String Quartet has collaborated are pianists Joyce Yang, Roger Woodward, Anne-Marie McDermott, Menachem Pressler, and Jeremy Menuhin; clarinetists Joan Enric Lluna, David Shifrin, Richard Stoltzman, and Eli Eban; soprano Elly Ameling; mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato; cellists Lynn Harrell, Sadao Harada, and David Requiro; and jazz greats Branford Marsalis, David Sanchez, and Andrew Speight. The quartet has worked with many composers including Aaron Copland, George Crumb, and Elliott Carter, and has long enjoyed a close relationship with composer-lecturer Robert Greenberg, performing numerous lecture-concerts with him annually.

The Alexander String Quartet added considerably to its distinguished and wide-ranging discography over the past decade, now recording exclusively for the FoghornClassics label. There were three major releases in the 2013-2014 season: The combined string quartet cycles of Bartók and Kodály, recorded on the renowned Ellen M. Egger matched quartet of instruments built by San Francisco luthier, Francis Kuttner (If ever an album had “Grammy nominee” written on its front cover, this is it.” –Audiophile Audition); the string quintets and sextets of Brahms with Toby Appel and David Requiro (“a uniquely detailed, transparent warmth” –Strings Magazine); and the Schumann and Brahms piano quintets with Joyce Yang (“passionate, soulful readings of two pinnacles of the chamber repertory” –The New York Times). Their recording of music of Gershwin and Kern was released in the summer of 2012, following the spring 2012 recording of the clarinet quintet of Brahms and a new quintet from César Cano, in collaboration with Joan Enric Lluna, as well as a disc in collaboration with the San Francisco Choral Artists. Next to be released will be an album of works by Cindy Cox.

The Alexander’s 2009 release of the complete Beethoven cycle was described by Music Web International as performances “uncompromising in power, intensity and spiritual depth,” while Strings Magazine described the set as “a landmark journey through the greatest of all quartet cycles.” The FoghornClassics label released a three-CD set (Homage) of the Mozart quartets dedicated to Haydn in 2004. Foghorn released the a six-CD album (Fragments) of the complete Shostakovich quartets in 2006 and 2007, and a recording of the complete quartets of Pulitzer prize-winning San Francisco composer, Wayne Peterson, was released in the spring of 2008. BMG Classics released the quartet’s first recording of Beethoven cycle on its Arte Nova label to tremendous critical acclaim in 1999.

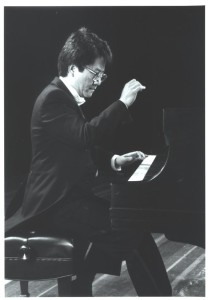

ALEX CHIEN, PIANO

Pianist Alec Chien received his Bachelor’s, Master’s and Doctoral of Musical Arts degrees from the Juilliard School of Music, studying under Adele Marcus. Grand Prize Winner of the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition and prize winner of the Sydney International Piano Competition, the Paloma O’Shea International Piano Competition, and the Affiliate Artists Xerox Piano Program, he has performed in solo and chamber recitals and as soloist with orchestras in countries on four continents, including Australia, Austria, People’s Republic of China, Greece, Hong Kong, New Zealand, Poland, Spain and Taiwan. Among the major symphony orchestras which he has been featured as soloist are the Philadelphia Orchestra, Pittsburgh Symphony, St. Louis Symphony, Utah Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, Buffalo Philharmonic, New Zealand Symphony, American Symphony and Hong Kong Philharmonic.

This spring semester of 2015 will be his last teaching year at Allegheny College as he is taking the early-retirement from that institution where he has been Artist-in-Residence and Professor of Music for 35 years. On campus, he has done two seven-concert series featuring the 32 Piano Sonatas by Beethoven and major works by Schubert and Chopin. A firm believer contributing to the Meadville community which had named Chien as “adopted native son,” he has been involved in local efforts such as Partner-in-Education, the Neighborhood Family Centre and Grief-Relief and Other Workshops (GROW). He and his wife, Brenda, have three daughters – Brianna, Mikayla Trousdale with her husband Joel and Bethany Fields her husband Mike. In the Fall of 2013, he joined the piano faculty of Carnegie Mellon University School of Music teaching Piano Literature & Repertoire for graduate piano majors, an endeavor he plans to continue.

Alec will always treasure his relationship with the Alexander String Quartet, with which he has had numerous wonderful collaborations at Allegheny and elsewhere. He wants use this afternoon’s Schumann Piano Quintet as a small token of his gratitude for their friendship.